A comparison of concepts from B.F Skinner’s “Beyond Freedom and Dignity” and Friedrich Nietzsche’s “Beyond Good and Evil”.

A comparison of concepts from B.F Skinner’s “Beyond Freedom and Dignity” and Friedrich Nietzsche’s “Beyond Good and Evil”.

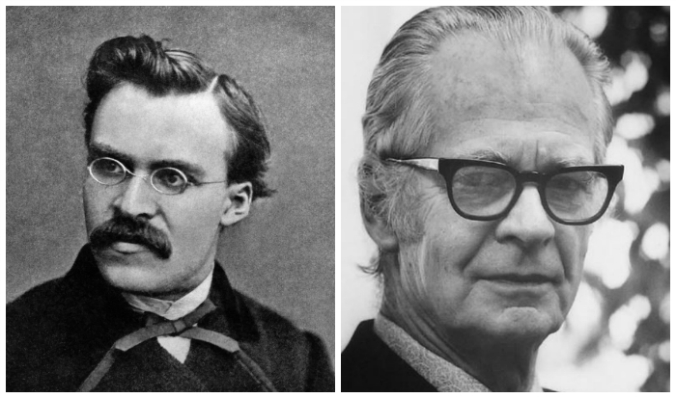

There was something about these two books that piqued my interest, and it was not until reading them again, together, that I saw that the similarities went beyond the titles. For those who have not been introduced to these individuals and their contributions; Friedrich Nietzsche was a 19th-century philosopher known for dealing with topics of existentialism and nihilism, and Burrhus Frederic (B.F) Skinner was a 20th-century psychologist and behaviorist interested in the natural science of behavior. Aside from the similarities in their names, and the names of the titles of their two works, few parallels have been drawn between these figures. I think there is a great deal of overlap, conceptually, between these two books, and although the conclusions of both authors diverge quite differently, the path and observations on the world and history are strikingly alike.

When it comes to B.F Skinner, I have been interested in the academic and philosophic lineage of his work, and existentialist philosophers have never been a reference or topic I’ve noticed before. Pragmatism, yes, and Roy A. Moxley (2004) did an amazing piece on the influences of Charles Sanders Pierce & John Dewey on Skinner’s conceptualization of the three-term contingency and broader behavioral selectionist theory. No Nietzsche. Not even once as far as I could tell. It raises some questions with me, then, in how these two books are so similarly constructed. Both seem to tackle a very similar topic, broad as it is, the actions of people, and their morality (which comes very close to dignity, in Skinner’s usage, in my estimation). They start with Western history and philosophy and even reference the same ancient Greek precepts as foundations to build their arguments and points from. Both appear to lead up to their current history and take into account their contemporary issues when presenting their philosophical conclusions. I am not a professional book reviewer or a literary scholar, so this process of literature exploration is outside of my wheelhouse, but I would like to lay out some pieces from both of these works to open the door comparatively. Both of these authors picked the right word “Beyond”. Both works present a series of presuppositions in their contemporary times and aim to progress past them rationally.

Skinner and Nietzsche: The Problems of Their Times

Context is important when reading and interpreting both of these authors. They were both big thinkers. Brilliant. Both wildly controversial. That tends to mean they had opinions, unpopular ones, but ones that they put out into the world rigorously supported by the assertions in their work.

Nietzsche was born in 1844, in Germany, and served in the Franco-Prussian war where he received grievous injuries that he never recovered from. “Beyond Good and Evil” was written after that. After the war, he wrote on the contemporary topics that he believed were essential to human progress and critiqued entrenched falsehoods that he believed were subverting people’s potential and lives. Morality was a big subject for him. Unlike other existentialist philosophers of his time, he was not so backseat and uncertain about it. He proposed that morality was separate from the Western religious belief systems and structures that were entrenched in society, and believed that willpower had the power to transcend these societal limitations. Traditional morality (societal and religious), to him, was making people weak. They needed to improve themselves, with their own morality and their own will, to be strong. In “Beyond Good and Evil” (1886), Nietzsche suggests that the words “Good” and “Evil” were malleable concepts that change over time, and were not fixed. Fear was a motivator for morality, he proposed, and that there was a mistake in believing that “mass morality” or the moral beliefs of the groups/society had any higher importance than an individual’s personal morality. Hold onto that thought.

Skinner’s work in “Beyond Freedom and Dignity” (1972) came from a very different time historically. In the 1970’s, the Cold War raised probabilities of worldwide escalation and catastrophe. In the first chapter alone, Skinner broached the topics of overpopulation, global starvation, nuclear war, and disease. Skinner did some philosophical work himself, but his main focus was as a psychologist and behaviorist interested in focusing on psychology as a natural science, to see human behavior as measurable and observable, and aim scientific pursuit as a “technology of behavior” to solve the problems of our time. In many ways, it was a utopian idea, and he expands on that vision in his fictional work “Walden Two”. Engineering society with this science was within humanity’s grasp. Skinner looked broadly at the ills of the world, and believed that there were some pieces of cultural and societal misunderstanding that was holding it back. Like Nietzsche, his observations strayed away from metaphysical interpretation. Skinner believed that natural sciences like physics and biology had made the leaps that psychology had not. People were still hung up on antiquated interpretations of human behavior. To Skinner, it was the environment and history of reinforcement/punishment that could be used to describe human action. He believed that mentalistic concepts such as “inner capacities” were circular, and lead to no useful distinction of a phenomenon or process that could benefit scientific discovery. Human behavior could be shaped by environment, and act on the environment as an operant. His work aimed to remove the ideas of absolute human freedom, and dignity in the sense of viewing the human being as the “fully autonomous man”; these were not practical representations of human behavior to Skinner. Full autonomy, free choice, with no input from the environment was nonsensical, which begged the question as to how free will was actually free when it was under the control of environmental stimuli, to begin with. Conceptualizing human behavior under the contingencies that Skinner proposed, including reinforcement and punishment, removes those antiquated and pre-scientific distinctions, and by removing them, people would no longer be under any false illusions and could take control of their behavior.

Where They Come Together, and Where They Differ

Both Nietzsche and Skinner’s line of thought come from a disagreement with the broader idea of humanity by contemporary society. For Nietzsche, it was a societal and religious misunderstanding of morality. For Skinner, it was a societal and historical pre-scientific misunderstanding of human behavior. Both “Beyond Good and Evil” and “Beyond Freedom and Dignity” do touch on similar points by their end: human behavior and morality. Both authors hit the same nail in two very different ways, both using historical context to do so and their own interpretation and findings from their own work and lives. There are some interesting divergences too, mainly on the topic of science and empirical materialism. B.F Skinner was very much interested in the material world and observable findings, which nearly 100 years prior, Nietzsche also had to deal with. In Nietzsche’s time, the late 19th century, these concepts were still budding, but rational observation of the world and the field of psychology was relatively recent in the form of psychoanalysis. He describes some of his ideas on the topic of science and the metaphysical soul in “Beyond Good and Evil”:

“Between ourselves, it is not at all necessary to get rid of “the soul” thereby, and thus renounce one of the oldest and most venerated hypotheses—as happens frequently to the clumsiness of naturalists, who can hardly touch on the soul without immediately losing it. But the way is open for new acceptations and refinements of the soul-hypothesis; and such conceptions as “mortal soul,” and “soul of subjective multiplicity,” and “soul as social structure of the instincts and passions,” want henceforth to have legitimate rights in science. In that the NEW psychologist is about to put an end to the superstitions which have hitherto flourished with almost tropical luxuriance around the idea of the soul, he is really, as it were, thrusting himself into a new desert and a new distrust—it is possible that the older psychologists had a merrier and more comfortable time of it; eventually, however, he finds that precisely thereby he is also condemned to INVENT—and, who knows? perhaps to DISCOVER the new.

Psychologists should bethink themselves before putting down the instinct of self-preservation as the cardinal instinct of an organic being. A living thing seeks above all to DISCHARGE its strength—life itself is WILL TO POWER; self-preservation is only one of the indirect and most frequent RESULTS thereof. “- Nietzsche (1886)

You can see here that Nietzsche is still strongly proposing that even in the area of science, psychology, and the soul, that willpower is an overlooked and undeniably important factor. I do find an interesting subpoint in there, in the process of invention and discovery by new psychologists, which nearly a century later would include Skinner himself. Although Nietzsche was strongly against the idea of science reducing everything to material reality, and I believe would take strong opposition to Skinner’s ideas on mentalistic representations of “soul” and morality, there is a great deal they share in their ways of tackling broader problems of their time, and interpretations of humanity as open to the future and unfixed. Humanity, to them, was not something that is and always will be the same. For very different reasons, Skinner and Nietzsche had a strange optimism of humanity in the wide and open possibility that either willpower, for Nietzsche, or contingencies for Skinner, could do for humanity as a whole.

B.F Skinner took a look at human morality himself in “Beyond Freedom and Dignity” when exploring the concept of cultural control, or behavioral control from the contingencies of a broader group, which included cultural, or rule-governed behavior and walked the line of evolution in both cultural and biological aspects both effecting one another to form a morality that was also “created” in a sense by evolution and sensitivity to cultural factors of control. Biological evolution making us sensitive to the evolution of cultural contingency. It’s a point that packs a punch.

“The practical question, which we have already considered, is how remote consequences can be made effective. Without help a person acquires very little moral or ethical behaviour under either natural or social contingencies. The group supplies supporting contingencies when it describes its practices in codes or rules which tell the individual how to behave and when it enforces those rules with supplementary contingencies. Maxims, proverbs, and other forms of folk wisdom give a person reasons for obeying rules. Governments and religions formulate the contingencies they maintain somewhat more explicitly, and education imparts rules which make it possible to satisfy both natural and social contingencies without being directly exposed to them.

This is all part of the social environment called a culture, and the main effect, as we have seen, is to bring the individual under the control of the remoter consequences of his behaviour. The effect has had survival value in the process of cultural evolution, since practices evolve because those who practise them are as a result better off. There is a kind of natural morality in both biological and cultural evolution. Biological evolution has made the human species more sensitive to its environment and more skilful in dealing with it. Cultural evolution was made possible by biological evolution, and it has brought the human organism under a much more sweeping control of the environment.”-Skinner (1972)

Two very different views, both denying a common cultural interpretation or framework for psychology, human behavior, and morality, but leaving a wide berth for future change, that in a sense is within humanity’s realm of control. I found those two shades of interpretation to be incredibly interesting, especially in morality. Remember that Nietzsche was well aware of the impact of “group morality”, and advised against its importance over the individual’s morality. Skinner also makes a nod to group forms of morality and seems to believe we are uniquely and biologically sensitive to it. I would love to have heard a conversation between the two of them on that. This is just the tip of the iceberg too. I suggest anyone who found their interest piqued to read both works and come to conclusions of your own.

By Christian Sawyer, M.Ed., BCBA

Thoughts? Comments? Questions? Leave them below!

References:

Moxley, R. A. (2004). Pragmatic selectionism: The philosophy of behavior analysis. The Behavior Analyst Today, 5(1), 108-125.

Nietzsche, F. N. (2007). Beyond good and evil. Place of publication not identified: Filiquarian Pub.

Ozmon, H. (2012). Philosophical foundations of education. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Skinner, B. F. (1971). Beyond freedom and dignity. New York: Knopf.

Image Credits: Wikipedia