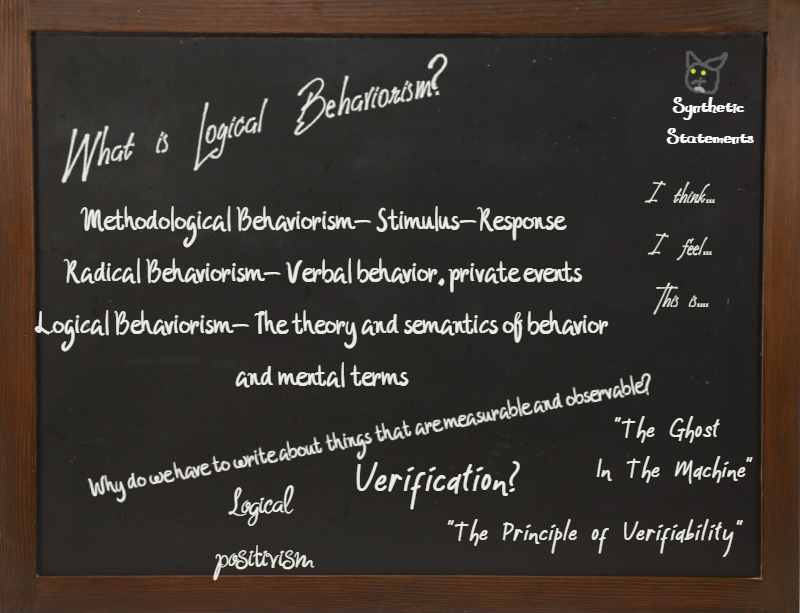

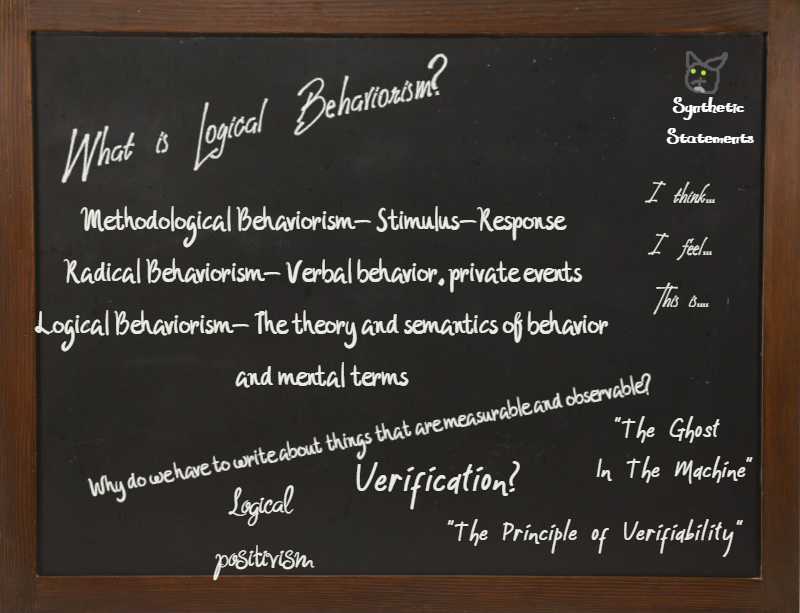

How we use language in behavioral science and psychology is important.

If you’ve ever studied psychology, or behaviorism specifically, have you ever asked?

“Why do we have to use observable terms for behavior?”

“Why do we define things in operationally and observational terms?”

These are also the questions that “Logical Behaviorism” was chiefly concerned with. If we are to treat psychology as a natural science, then proponents of logical behaviorism would suggest the language, theory, and semantics used in this process should reflect this.

Logical behaviorism is perhaps one of the more obscure branches of behaviorism as a whole, but whose history is closely tied with the more familiar methodological or radical behaviorist schools of behavioral thought. Logical behaviorism originated in the early 20th century when scientists and philosophers aimed to establish psychology as an independent and experimental natural science. Like methodological (classical) and radical behaviorism, logical behaviorism shared the focus of objectivity and reliance on measurable techniques for observation, data collection, and the rejection of introspective-heavy mentalistic explanations.

Where logical behaviorism differed from other behaviorist branches, is that its was concerned primarily with the scientific usage of language and semantics in psychology. The early proponents of logical behaviorism aimed to completely differentiate the objective and scientific behavioral psychology of the time, from the popular Freudian and Jungian introspective and mentalistic psychological writings. Because of this, logical behaviorism is often seen as more a philosophical psychology than directly empirical. Many of the positions of logical behaviorism are hidden in the works that modern behavioral practitioners are very familiar with. They inform the attitudes and (even in some cases) suspicion towards mentalistic language in day to day practice.

“The Ghost In The Machine”

The philosopher primarily known with the development of logical (or analytical) behaviorism was Gilbert Ryle. For most of Ryle’s academic career, he was focused on the dismissal of the mind/body distinction (Cartesian dualism, or substance dualism) that was, and still is, extremely common in psychological and philosophical writings and thought. You likely come across dualistic language like this often in even the briefest psychological conversations, which infer that mental states (thoughts, feelings, imagination, etc) occur in a hidden, or non-physical area or dimension of the mind, apart from physical and physiological processes. Ryle disagreed with this.

Belief, for example, would not be seen as an airy mental element of cognition, but something completely within the explanatory processes of biology, according to Ryle. Gilbert Ryle believed that there was a risk in these distinctions, that lead philosophy and science astray, chasing separations that did not actually exist.

Gilbert Ryle’s writings (“The Concept of Mind”) often took aim at these dualistic notions, taking the example of a mental effort of “will or volition” which then transformed into physical action (mental thought leads to physical action), as a widely held mistake. He calls these mistakes the “dogmas of the ghost in the machine”. The very study of the separation between mind and body were a waste of time, and fruitless, accord to Ryle because they were category mistakes; separated more by their linguistic definitions than any real qualities. Instead, Ryle proposed that all actions and behavior are physical in nature, and that there are propensities and dispositions that can be explained entirely by the behavioral actions of an individual to seek or avoid the stimuli involved.

For example, there would be no mind/body distinction between wanting breakfast, and cooking breakfast. For Ryle, there was nothing in some immaterial mental state that spurred the cooking of breakfast. To speak or imagine this cause-effect relation, leads to a principle misunderstanding of the event and behaviors themselves. If we tried to study this event using those terms, we would have to chase down the immaterial mental state, or depend that it existed outside of physical or observable evidence, as a part of our study. This could lead to circular reasoning very quickly. Chasing this “ghost in the machine” bears no scientific fruit.

Ryle does not preclude that there are physical process of behavior and action which can not be seen (which he calls propensities and dispositions), but that these do not reside in some immaterial state, and these propensities/dispositions can be discovered through the modes of observable behavioral action. This shares some similarity with the “private mental events” of B.F Skinner’s radical behaviorism, but does not go as far into speculation of functional and environmental relations as Skinner had. Ryle did use a behaviorist theory of mind, but one that was focused on the language of behavioral processes.

It is fair to note, however, that Ryle’s work has received criticism because the focus on language dependent on observable action may be too restrictive. Critics of Ryle’s work have often brought up that there may be a bigger distance between internal or “mental states” and verifiable behavioral actions. It is possible for most people to imagine a situation where someone is happy, while not showing outward “behavioral actions” or signs of happiness. The reverse is also true. Movie actors for example, act in ways that do not accurately represent their “mental state”. An actor’s portrayal, in some cases, does not reflect the actual propensities and dispositions that Ryle would infer from their behaviors using his methodology. It is historically more practical to understand that Gilbert Ryle’s work (especially “The Concept of Mind”) has greatly influenced how behaviorists treat the mind/body distinction, dualism, and mentalist language in their scientific writing, but that Ryle’s theories and positions were influential in part, not as a whole.

The Vienna Circle and Logical Positivism

Where might the “Logical” part of “Logical Behaviorism” come from? Why would it be called that? The answer lies in an earlier philosophical endeavor called logical positivism, developed by a group of late 19th century philosophers called the Vienna Circle. The connection between this philosophy of logical positivism with behaviorism, is that behaviorists seek a framework of language that can accurately reflect the observable facts of behavior. Without this framework of language, misconceptions, circular reasoning, and arguments about the linguistic minutiae of the scientific literature could bog the whole study of behavioral psychology as a natural science down. Dependable language leads to fewer misunderstandings in the scientific literature, and potentially better replication of what is being tested and studied.

Logical positivists, and the later logical behaviorists, wanted linguistic precision in the study of psychology and behavior. A precise language could lead to better verification of observable events. The philosophers of the Vienna Circle, called this the “principle of verifiability”, and that there should be no statements in the literature that could not be verified empirically, or at the very least is capable of verification at a future date. There are certain things that can be stated which can not be verified immediately, but allow, in their wording, a means to verify them at a later date. For example: “Next Tuesday it is going to rain.”. This statement can not be verified right now, but does allow for verification. This was important to logical positivist philosophers, and later the logical behaviorists. This is a staple of most empirical behavioral research, and is often taught as a maxim without needing explanation. It was not always the case. Without employing the “principle of verifiability”, any unverifiable statement could be used as premise with impunity. Unverifiable statements (mentalistic or substance dualistic statements for example) can not be disproven objectively, because they allow no empirical way to do so. To the logical behaviorists, these statements are hardly helpful to scientific literature.

The philosophers, scientists, and mathemeticians in the Vienna Circle, chiefly Rudolf Carnap, Moritz Schlick, Herbert Feigl, Felix Kaufmann, and A. J Ayer, developed this form of analysis using the “principle of verifiability” taking heavily from earlier philsophers like Ludwig Wittgenstein, to design a way for statements to be able to be analyzed. You likely see these types of statements in empirical and scientific research all the time without realizing it. The early logical positivists differentiated between what they called “analytical statements” and “synthetic statements”. Analytical statements could be true simply because it logically follows from their meaning.

Example (Analytical Statement): All circles are round.

Of course they are.

Synthetic statements, on the other hand, require some empirical verification in order to be confirmed or proven true. These statements when using the “principle of verifiability” can be verified.

Example (Synthetic Statement): “This cat has gray fur and is wearing clothing.”

Let’s take a look.

Well, look at that. We can verify this statement with observation.

Both of these statements are important to distinguish between, but do not hold equal weight within logical positivism, and logical behaviorism. To the philosophers of the Vienna Circle, and most logical positivists, synthetic statements are what should be first and foremost of importance. Synthetic statements make claims about reality, which can be tested, and that is incredibly important when it comes to natural sciences. The use of analytical statements are more trivial, to logical positivists, because they bring no new information. Logical behaviorism shared in the logical positivist belief that true propositions and statements should be capable of scientific verification in order to be useful scientifically.

Logical Behaviorism takes from this the focus of synthetic statements about behavior, which are observable and measurable. Even when dealing with “mental concepts” or “private events”, the importance is in the language being used to create propositions that can be verified.

To Sum It Up: Logical Behaviorism Is About Language

To a logical behaviorist, concepts like the mind, and thoughts, and feelings, and imagination, all must be described in ways that have an observable or verifiable attribute to them in order to be useful scientifically. Logical behaviorism was developed in a time of strong mentalistic terminology, where circular reasoning towards behavior was common, and human action as a whole was sometimes treated as indescribable, and the mind in some ways untouchable by science. To the logical behaviorist, the semantics, or language of what we study and talk about when we try to describe behavior, even internal processes, must in some way be verifiable, or objective, in order to be useful in a scientific sense.

How we state things, and how we propose things, is important. To be too loose with language in this area invites misunderstandings, as Gilbert Ryle pointed out, or lacks the ability to be later verified, as the logical positivists believed. To make a statement that is observable, measurable, and can be verified is what many logical behaviorists believed would bring psychology, and the new branch of behaviorism, closer to that goal of being a natural science.

I hope you enjoyed this brief look at the history and reasoning behind the Logical Behaviorism theories, and the many influences. This is by no means an exhaustive dig into the rich topic, but a broad touch on the vary complex psychological and philosophical roots which all came together to bring about what we know about behaviorism and psychology, and what logical behaviorism still shines through these many decades later.

Comments? Questions? Thoughts? Leave them below! Don’t forget to follow!

References:

Clark L. Hull. (2019, February 21). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clark_L._Hull

Fancher, R. E., & Rutherford, A. (2017). Pioneers of psychology. New York, NY: Norton & Company.

Hull, Clark L. Principles of behavior. (1964). New York.

Ozmon, H. (2012). Philosophical foundations of education. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Ryle, G. (1949). The concept of mind. New York: Barnes & Noble.

Skinner, B. F. (2015). Verbal behavior. Mansfield Centre: Martino Publ.

The new encyclopaedia Britannica. (1977). Chicago, IL: Encyclopaedia

Britannica.

Image Credits:

Artwork, and photography are originals by the author Christian Sawyer.